A few months ago, I responded to a call from

to discuss quit lit on her podcast (featured here on her substack, ).When I was reading the comments and other replies, I saw other Substackers (many of whom I admire) naming all my favorite contemporary Quit-Lit books: The Luckiest Club (

), Quit Like a Woman (), This Naked Mind (Annie Grace).Some of the lesser known ones, too — Blackout: Remembering the Things I Drank to Forget (

), My Fair Junkie: A Memoir of Getting Dirty and Staying Clean (Amy Dresner), The Recovering: Intoxication and Its Aftermath (Leslie Jamison).Julie’s call had asked for books that helped you get sober, but also books you might want to revisit. This got me thinking about the lesser known “Quit Lit.”

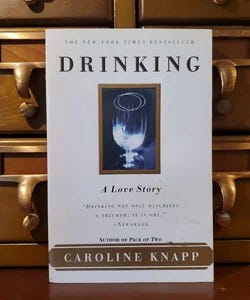

I remembered Caroline Knapp’s Drinking: A Love Story. It’s almost like the OG Quit-Lit : Quit-Lit before quit lit was quit lit. A literary memoir, published in 1996, before Instagram, before TikTok, before publishers required (or strongly recommended?) 10,000 followers to publish a book.

Drinking is a literary piece — Drinking isn’t selling anything, it isn’t even pushing sobriety. It is as simple as its title : it is a love story.

I first read Drinking: A Love Story in 2011, when I was in grad school. I remember sitting on the bed in my one-bedroom apartment above the bar I would frequent (it was called the Garden, and I loved it) and just thinking, I am so fucking sunk. Much the way I felt when I read Holly Whitaker’s Hip Sobriety, and later, when I read the chapter More About Alcoholism in the book of Alcoholics Anonymous.

What I thought was: this story is my story.

I had recently fallen into something of a funk (from which I am now emerging) but it was one of those long weeks-long nights where I just have to feel, feel, feel for fucking ever. One of those times that I think, God, I don’t want a drink, but is there anything that can make this present a little less present-y?

I think of the character on “Working Moms” who said she was fantasizing about getting into a car accident, you know, not like, a really bad one, just one that would let her have a little vacation, a nice little couple day stay at the hospital.

I was under the impression that this sadness had come about from overwhelm, as the holidays had just passed when we had a week of snow days (read about it here where I’m trying to find my gratitude), three weeks of track out (year-round school), and another series of snow days, but I actually think it was re-reading this book.

This book spoke to — or rather reminded me — of the deep wounds that I have yet to address. I have addressed some of these things in my recovery work, but there are still wounds remaining — particularly those that involve: men, food, blackouts, and the damage done to the brain’s natural rhythms from alcohol.

The peeling of the trauma onion, the reveal of things that still need tending and healing, is still very much active in my life, just a few years into this sobriety thing.

Men

“So when Roger took me out to lunch a few weeks later, and when he kissed me in the car afterward, I felt shocked and confused and appalled and also, oddly, victorious. The feeling was: I got what I wanted, I won. And because I understood I’d participated in the game, because I knew I’d worked on some semiconscious level to draw him in, I somehow deprived myself of the ability to get out cleanly. How can you say no when you’ve worked so hard to make someone else say yes?” (94)

This entire chapter, aptly titled “Sex,” gutted me. It was as though, through this call for podcast guests, the universe was telling me: it’s time to heal this part of you.

In a recent IFS session, in fact, my therapist advised me to visit the version of myself who had endured a sexual assault by a boyfriend who I had loved very much.

When I approached this “part” or this old version of myself in my minds’ eye, I saw her face-down, in dirty clothes, sitting on the ground, knees up, resting her head on her knees. When I explained to her that it wasn’t her fault, that even if she had made him mad, or done whatever it was she had done, she — just in her humanness — did not deserve to have had done what was done to her, she looked up at me.

Then she motioned to a door behind her. “What about them,” she asked. She opened the door and there was an auditorium of youthful Kristen’s. All of them teeming about. They were all 19, 20, 21, 22. They hadn’t done anything wrong, and perhaps nothing malicious had been done to them, but things that perhaps someone with the kind of self worth I have today would not have needed to partake in, or not know how to say no to.

An auditorium full of splintered soul fragments, all damaged during those very young drinking years, I thought.

Those are the parts of you that you need to forgive yourself for, my therapist said. The younger me who, as Caroline Knapp did, asked this question and couldn’t quite come up with an answer while still in active addiction: How can you say no when you’ve worked so hard to make someone else say yes?

Food

“These are women who toss around the phrase food issues a lot, as in “I had a lot of food issues back then,” or “My food issues are really up these days.” Anyone who’s struggled with a distorted body image of hyperconsciousness of weight (and that’s most women I know) understands what those words mean: they’re shorthand for self-hatred and self sabotage, for loss of control or fear of it, for all the other particularly female rages and fears that, according to the New York Times, compel half the population to shell out an estimated $33 billion a year on diet and weight loss programs.

And while they’re at it, a few extra bucks on booze.” (135)

The joke I had for many years: body image issues? You’re still stuck on that? I’ve got bigger fish to fry.

In my early drinking years, I ate the same thing every day: 2 eggs and a piece of toast, a yogurt for lunch, and a SlimFast for dinner. At the end of the night, I would pour myself a vodka and I remember sitting outside, sipping my vodka over ice, hungering, waiting, wanting to eat those delicious two or three Manzanilla olives.

Later, always wanting to drink on an empty stomach to get the best buzz, then finding evidence of several devoured quesadillas or other random shit in the kitchen the morning after.

And today, standing in my kitchen, shoveling handfuls of peanut butter M&Ms in my mouth.

Quit the things in the order they’re killing you, I recall: booze, cigarettes, sugar (Julie and I have a fun little bit on sugar near the end of the podcast, right at the one hour mark).

Food issues, indeed.

Blackouts

“Elaine used to call it the “Uh-oh’s,” that feeling of waking up in a haze after a night of heavy drinking, regretting things you blabbed about, or not being able to account for whole chunks of time, wondering what you’d done. Uh-oh: did I say something really bad? Have sex with someone? Kill anyone driving home? I was glad she had a name for it: it happened, I supposed, to everyone.” (163)

When I tried to make amends to my ex-husband, he said to me: You don’t even know what you’re apologizing for.

And it’s possible — probable? perhaps certain? — that I didn’t entirely know. So many hours are lost, gone, disappeared. Evaporated. I was pouring a drink, and then, Poof. It was morning.

So, as a means of living amends, I don’t take a drink today, or any other day.

The Brain and Dopamine

“Essentially, drinking artificially activates the brain’s reward system: you have a martini or two and the alcohol acts on the part of the brain’s circuitry that make you feel good, increasing the release of the neurotransmitter dopamine, which is central to feelings of pleasure and reward. Over time (and given the right combination of vulnerability to alcoholism and actual alcohol abuse), the brain develops what are known as “compensatory adaptations” to all that artificial revving up: in an effort to bring its own chemistry back into its natural equilibrium, it works overtime to decrease dopamine release, ultimately leaving those same pleasure/reward circuits depleted.

A vicious cycle ensues: by drinking too much, you basically diminish your brain’s ability to manufacture feelings of well-being and calm on its own and you come to depend increasingly on the artificial stimulus — alcohol — to produce those feelings” (126).

This is perhaps the most direct and best description of the brain and dopamine and alcohol that I have come across (Julie and I chat about this briefly around minute 54:45).

Drinking: A Love Story remains a touchstone in my repertoire of Quit Lit — and one that has been somewhat forgotten. Honest, tough, gentle, and unflinching — and lastly, a book that is not selling you a recovery program. Knapp died sober, but quite young, of lung cancer in 2002, young, at the age of 42, just 6 years after Drinking was published.

You can check out the conversation Julie and I have about Drinking: A Love Story on her Like A Normal Person podcast series here. Thank you again for inviting me to be a guest on your podcast,

, and congratulations again on your book, Like A Normal Person!

I have read this post three times now. Because it’s making me feel less alone. More normal. More OK.

men, sex, blackouts. Those were my issues when drinking. I was a binge and blackout drinker. If I drank, 90% of the time, I blacked out.

I’m so sorry-and so sad-that a Boyfriend you loved did that to you.

Sadly, I think too many women who drank have similar stories. Mine were committed by men I didn’t know at all or very well. I still feel gross when I think of what young Rosemary endured by men who took advantage of her inability to consent.

I haven’t read Drinking A Love Story, but I’m going straight from this comment to my library app to see if I can borrow it.

And your past versions of you ? Dang. I want to hug every one of them. This is such powerful,gorgeous, heartbreaking imagery & writing.

I can’t wait to listen to this episode with you & Julie.

“this story is my story.” That, for me, has been what keeps me in this game, the long game. Every time I hear my experiences verbalized by another woman, I feel seen. Understood. Less fucked up.

We’re not fucked up. We just learned how to run away from ourselves, habitually.

That auditorium of Kristens - hugs to every earnest version of you. I’ve been doing some revisiting to past Allisons and it really feels hard to hold.

This essay is so important and so gorgeously written. I’ll return here when I’m spinning or feeling lost.

Thank you for sharing.

I think I’ll revisit Knapp, too.